INE has just published the Quarterly Sector Accounts for the third quarter, showing that for the first time in any quarter this century the net lending of the Portuguese economy has turned positive. In the year to 2012Q3, the net borrowing of the Portuguese economy amounted to just 1.1 billion euro, when in the year to 2011Q3 those needs amounted to 12.3 billion euro. An adjustment of 11 billion euro, or 6.7 percent of GDP, in one year, is an enormous external adjustment, and it was much higher than expected. For instance, the May 2011 IMF projections forecasted that by 2016 the Portuguese economy would still have external net borrowing of 1% of GDP. Why was Portugal's external adjustment so strong in the first year of the adjustment program?

The net lending of the Portuguese economy is equivalent to the sum of the current account and the capital account of the balance of payments. Since, by definition, the balance of payments always balances, it is also equivalent to the negative of the financial account. When there are no financing constraints, the real economy determines the financing needs, i.e. the top part of the balance of payments determines the bottom part. However, in a financing crisis, when there are strong financing constraints, the availability of financing is binding, implying that it is the bottom part of the balance of payments that determines the top part. The domestic agents must reduce their expenditure to the available financing, even if they had higher expenditure plans.

The INE data provides some evidence that financing was a binding constraint for Portuguese households. In the past, private consumption has always been smoother than disposable income, implying that in recessions consumption fell by less than disposable income, and the savings rate declined. However, this was not the case in the year up to 2012Q3. Private consumption fell by 3.4%, while disposable income fell by only 1.4%, relative to the year up to 2011Q3. While negative expectations may have played a part, this anomalous behavior is likely to have been determined by a binding financing constraint. Non financial corporations have also decreased their financing needs by 5.3 billion euro in the same period, while gross value added has fallen by 1 billion euro. It seems that the Portuguese economy has been operating under a binding external financing constraint, which is not surprising if one remembers that the immediate cause for the signing of the Financial and Economic Adjustment Program with the troika was the lack of financing for the Portuguese government and banks.

If the Portuguese economy is under a binding external financing constraint, and if the financing constraint is not specific to any domestic sector, then there is full crowding out of fiscal policy. Any increase in the public sector financing needs must be matched by a equivalent reduction in the private sector financing needs. In other words, if the external financing constraint is fully binding, the size of the budget deficit does not have any influence on domestic demand. If this is the case, then the fiscal policy that would foster private consumption and investment would be a reduction of the budget deficit. Under these circumstances, the government could reduce public expenditure as quickly as possible, in order to allow for sufficient financing to be available for the private sector, without decreasing GDP or increasing unemployment.

Monday, 31 December 2012

Thursday, 20 December 2012

information on the Portuguese economy

Students at Nova School of Business and Economics produce regularly analysis and data on the Portuguese economy, in areas connected closely with the Memorandum of Understanding, so we have now:

- a report on the Portuguese banking sector,

- a report on the Justice System,

- a report on the labour market,

- a report on the housing market

- a report on the Portuguese banking sector,

- a report on the Justice System,

- a report on the labour market,

- a report on the housing market

Wednesday, 12 December 2012

Facts on nontradables in the Portuguese economy

The rise of nontradable sectors has been mentioned as one of the causes of low economic growth and external imbalances at the root of Portugal’s current predicament – João Ferreira do Amaral and Vítor Bento were among the first to ring that alarm bell. The ECB, the EU and the IMF (troika) seem to share the same view. The 2012 OECD Economic Survey of Portugal has also stressed the need for eliminating the distortions that tilted the Portuguese economy towards low-productivity domestically-oriented sectors. Recently, the President, Aníbal Cavaco Silva, and the Minister of the Economy, Álvaro Santos Pereira, have also been calling for the re-industrialization of the Portuguese economy.

In a joint paper with Pedro Bação, we describe the main trends and jumps in the evolution of nontradable sectors, since the mid-1950s, using four different databases to shed light on different dimensions of this issue. From our analysis we stress the following points:

1. Despite the pattern of the growth of the share of services being similar to that observed in other developed countries, since the early 1990s it has been significantly larger than in most countries.

2. The shift to nontradables in Portugal has been fast and it occurred essentially at the expense of agriculture in the period 1953-95, and essentially at the expense of industry in the period 1995-2009.

3. In 2009, the share of nontradables (defined as the sum of services plus construction) in total GVA reached 68%, if we exclude open service sectors, and 81.1%, if we treat all service sectors as nontradable.

4. More than half of the change towards nontradables since joining the European Union took place in the period 1988-1993.

5. Finally, we show that construction and services facing a strong Government demand were the main drivers of the increasing weight of nontradables in the Portuguese economy since 1986.

Tuesday, 11 December 2012

TAP: post-scriptum

I am glad and

grateful that Exame Expresso and Jornal de Negócios yesterday followed up on

the issue of TAP’s valuation in Gérman Efromvich's offer. They did the public interest a

huge service. Mr. Efromvich’s bid was greedy, but he is pragmatic. He knows

that if there is a second competitive sale process he is very unlikely to win

the prize (TAP) even if he bids €2bn-€3bn and he would have to wait perhaps a

year.

He now

faces a dilemma:

·

He

may well try to “get the deal clinched” and “everybody happy” by offering anywhere

from €500mn to €1bn (rather than €20mn). But he knows this will leave the sell

side feeling like fools;

·

He

may lobby in the expectation that the government powers ahead with the current offer – a real

possibility with this government - , but this likely is, from his perspective,

too risky a gamble;

·

He

could, of course, walk away, … but ...

·

He

could also bid €2bn-€3bn and argue that the government would not get more if it

decides to reopen the sale process.

So, how

will this saga play out?

For the

record, in my view, given the role of TAP to Portugal’s export sector, the

government shouldn’t sell TAP at this point.

Sunday, 9 December 2012

Germán Efromovich’s offer for TAP

According

to Jornal

de Negócios, the only bidder for the privatization of TAP has made a

revised final offer to acquire TAP which, not surprisingly, is lower than the

original non-binding offer since he is the only bidder for TAP. According to JN,

the government is disappointed but wants to negotiate which says a lot about

whoever is handling the negotiation on the Portuguese government side, as I

shall argue below.

Jornal de

Negócios states that the Germán Efromovich is offering to assume TAP’s debt of

€1,2bn (TAP’s net debt is in fact €1,05 bn, about 60% of which concerns its

fleet leasing debt) and to inject €300 mn in the company. He would then pay as

little as €20 mn to the government for the (complete?) ownership of the company,

but according to Jornal de Negócios he wants to pay even less than the €20mn.

Maybe there

are additional details not reported by Jornal Negócios, because typically this

type of acquisitions are based on EBITDA (Earnings before interest depreciation

and amortization) multiples. But if Jornal de Negócios is correct, Gérman

Efromovich’s bid looks very very low – TAP seems much more valuable, as I shall

argue below.

Ricardo

Arroja wrote

a very interesting post in Insurgente about TAP’s privatization, which

called my attention because he looked at the balance sheet of TAP. Thus,

Ricardo Arroja’s post made me curious and I analyzed TAP’s balance sheet.

Now, first,

one correction to Jornal de Negócios. Germán Efromovich is not assuming any of

TAP’s debt. TAP’s balance sheet already assumes that debt, i.e., TAP has assets

which are worth about €300 mn less than its liabilities (including the €1,2bn

debt). Any buyer would likely keep TAP’s debt on its balance sheet since in

this way the buyer can maximize the return on investment and optimize his tax

bill.

Now

everyone assumes that TAP is over-indebted and worries about TAP’s negative

equity. But businesses do not need positive equity levels to function. What

they need is positive cash flows. TAP has positive operational cash flows and

EBITDA and has managed to stabilize debt levels.

More

important, TAP’s debt levels do not seem high at all for a company of its

dimension. TAP’s interest and leasing costs are a small fraction of the company’s

total costs, which means that capital, while important, is not the key variable

for TAP’s business.

Perhaps the

following example will clarify my point. If TAP uses half of the €300mn capital

injection proposed by Germán Efromovich to increase its working capital, and

the other half to reduce its stock of debt, its financing costs would fall by

about €9mn, or by about 0.4% of the company’s total costs, i.e., by a

negligible amount. This signals that while further capital is helpful – and might

help TAP expand or better hedge fuel cost risks - , TAP will likely be able to

thrive in the future even without any capital injection.

I do not have information on TAP's most recent financial numbers. However, the 2011 balance

sheet indicates that TAP is in a situation where slight operational

improvements in revenues and slight decreases in costs will result in a marked

improvement of its results and reflect favorably on its balance sheet. A 5%

increase in revenues and a 5% decrease in operational expenditures will likely result

in improvement to EBITDA of about €250 million per year, or about 70%-80% of

what Germán Efromovich wants to pay for TAP.

TAP’s

EBITDA in 2011 was €106mn. A purchase price based on a multiple of 10 of the 2011

EBITDA seems a fairly run of the mill (modest) valuation for the company. It would

mean TAP would be worth about €1bn, which less the €300mn capital injection means

a sale price of about €700 mn. But if an improvement in EBITDA of €250 million relative to the 2011 performance is assumed, then TAP would be worth €3.2bn

(already net of the capital injection).

But I am

likely being conservative here. Gérman Efromovich owns airline companies. This means

he is likely to obtain significant synergies between his different airlines. Greater synergies mean larger EBITDAs, which

mean TAP is likely much more valuable for this entrepreneur than the €3bn I estimate

above.

In my view,

TAP is on course – bar unexpected shocks - to become systematically profitable

in the short term. Germán Efromovich will get his investment back very quickly.

He is a shrewd investor and if he succeeds in his bid he will have a very high

return on his investment.

But he must

be innerly laughing at the apparently “naïve” selling side (i.e., the Portuguese

negotiators) who are begging him to

condescend to give a few more millions of euro or even possibly willing to pay

Germán Efromovich to get rid of TAP.

Finally, TAP

is one of the country’s largest exporters and plays a key role in one of the

country’s leading export industries (tourism). It also is one of the main

airlines for connections to Portuguese language countries in Africa and South

America (CPLP), some of which are also Portugal’s fastest growing export markets.

Portugal’s adjustment requires a huge improvement in external trade for the

current or any other adjustment program to succeed. From a macroeconomic policy

making point of view one does not want to play around casually with one of the

key players in our export industry precisely at this time in History. But none

of this appears to be of any relevance to our decision makers.

Tuesday, 4 December 2012

Banking Union and the supervision of 6000 banks

"Nobody believes it will work. Nobody believes any institution will be able to supervise 6,000 banks.” Wolfgang Schauble, Germany’s finance minister, FT 2012

"Our specific responsibilities include the oversight of about 5,000 bank holding companies, including the umbrella supervision of large, complex financial firms; the supervision of about 850 banks nationwide that are both state-chartered and members of the Federal Reserve System (state member banks); and the oversight of foreign banking organizations operating in the United States."Chairman Ben S. Bernanke,The Federal Reserve's role in bank supervision, Before the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C. March 17, 2010I concede that 6000 > 5850. Not that 6000 >>> 5850.

P.S.

Question: how many Polish banks are...Polish?

Sunday, 2 December 2012

Portugal and the welfare state, step 1

A recent article in the Financial Times (Portugal grapples with cost of welfare state) addressed recent statements by the prime minister on the reforms in the public sector.

The starting point was the statement a couple of weeks by the minister of finance on the (apparent) difference between what people want to pay in taxes and the welfare state benefits they want.

The discussion on the role and size of the state and how it is funded (and not the components of the welfare state) is a much needed debate in Portugal. But it cannot be done until February or March if it is supposed to include the views and desires of the Portuguese population and if its to go beyond cut expenditures across the board.

The challenge for the discussion is how to be cut in terms of what the Government does - not only the always-mentioned quest for efficiency in Government provision of services but also which ones are to be provided by the Government.

This goes beyond knowing which charges people should pay when using Government services. And forces the need for clarification of concepts and roles of Government spending. One the more common errors of perception, which is also present in the financial times article, is people saying they could afford to pay more for health care at point of use - meaning usually that people accept income-based payments at the point of use. Fine. But the mistake is that such charges are usually a very small portion of total funding required, user charges account for less then 2% of total funding needs in the National Health Service. Increasing user charges to cover say 20% would probably lead most people to complain about it. Even the largest single user charge, use of emergency room in central hospitals, is about 10% (or less) of average cost of such episode - this is 20€ user charge mentioned in the FT article. The second aspect of this mistake is conceptual - redistribution should mainly be done at the funding level, not at the point of use. If there is some correlation between income and need of health care (use), then payments at the point of use according to income may help, but they also destroy the insurance value of protection against uncertainty of health care expenditures. And this role is neglected (wrongly) in most popular statements.

From other areas we are likely to face good arguments for Government intervention, meaning that a careful discussion needs to be made.

Recognizing the importance of this discussion the prime minister said that a baseline proposal for cuts will be provided by February but changes are possible until the Summer, before the next budget proposal is built. This is reasonable. Sets a default situation, and then it is up to the political forces and to society to improve on it. Being too assertive at this stage will not allow for a proper discussion. Let's hope the Portuguese people can do it.

The starting point was the statement a couple of weeks by the minister of finance on the (apparent) difference between what people want to pay in taxes and the welfare state benefits they want.

The discussion on the role and size of the state and how it is funded (and not the components of the welfare state) is a much needed debate in Portugal. But it cannot be done until February or March if it is supposed to include the views and desires of the Portuguese population and if its to go beyond cut expenditures across the board.

The challenge for the discussion is how to be cut in terms of what the Government does - not only the always-mentioned quest for efficiency in Government provision of services but also which ones are to be provided by the Government.

This goes beyond knowing which charges people should pay when using Government services. And forces the need for clarification of concepts and roles of Government spending. One the more common errors of perception, which is also present in the financial times article, is people saying they could afford to pay more for health care at point of use - meaning usually that people accept income-based payments at the point of use. Fine. But the mistake is that such charges are usually a very small portion of total funding required, user charges account for less then 2% of total funding needs in the National Health Service. Increasing user charges to cover say 20% would probably lead most people to complain about it. Even the largest single user charge, use of emergency room in central hospitals, is about 10% (or less) of average cost of such episode - this is 20€ user charge mentioned in the FT article. The second aspect of this mistake is conceptual - redistribution should mainly be done at the funding level, not at the point of use. If there is some correlation between income and need of health care (use), then payments at the point of use according to income may help, but they also destroy the insurance value of protection against uncertainty of health care expenditures. And this role is neglected (wrongly) in most popular statements.

From other areas we are likely to face good arguments for Government intervention, meaning that a careful discussion needs to be made.

Recognizing the importance of this discussion the prime minister said that a baseline proposal for cuts will be provided by February but changes are possible until the Summer, before the next budget proposal is built. This is reasonable. Sets a default situation, and then it is up to the political forces and to society to improve on it. Being too assertive at this stage will not allow for a proper discussion. Let's hope the Portuguese people can do it.

Friday, 30 November 2012

The IMF’s rosy public debt projections*

I have analyzed and replicated the IMF’s Debt

Sustainability Framework for Portugal provided in the adjustment program review

reports (a table in the IMF Country Reports for Portugal). This IMF review

report table contains the IMF projections for the levels of Portugal’s public

debt from 2012 through 2030. The IMF review reports are the data sources for

all graphs below.

In my opinion, the IMF’s debt projections should be interpreted as the “objectives” for the evolution of the levels of public debt, should the adjustment program perform as planned.

As is well known, the key condition to assure debt sustainability is that the economic (nominal/real) growth rate is higher than the (nominal/real) interest rate on the stock of debt.

The key points of my short analysis are:

- Even if the everything goes according to the troika and government plan, public debt dynamics seems barely sustainable, falling below 100% of GDP only around 2025

- Each review has resulted in the worsening of the public debt trajectory (please see figure below).

- This is to some extent explained by increases in the initial stock of debt – for example, resulting from Eurostat-mandated changes in the universe of public sector enterprises included in the consolidated accounts of the public sector. But one additional important explanation is that the adjustment program has had a worse than expected impact on economic growth resulting in lower growth projections with each review (please see figure below)

- Maybe I missed something, but I could not replicate the debt levels for 2014 and 2015. The difference in 2014 and 2015 debt levels explains 94% of the deviation between my 2030 estimates (debt at 88% of GDP) and the IMF's 5th review projection (84.8% of GDP)

- The IMF has, in each successive review revised interest rates lower (see figure below). (Addendum) Francesco Franco pointed out that at least some of the reductions in interest rates follow from the reduction in EU loan rates to Portugal - the 215 basis point EFSF margin was reduced to 0 - (Bloomberg’s David Powell recently noted what he called the "mysterious" reduction in interest rates from the 4th to the 5th review report, and this had me look at the evolution of interest rates in all IMF review reports).

- Moreover, the debt trajectory is not really robust (see figure below). In fact, if nominal growth rates from 2012 turn out to be lower by one percentage point and the average interest rate from 2015 on to be higher by one percentage point than assumed by the IMF, the debt levels would rise by 2030, not fall.

The “Fazit”: Portugal’s sovereign debt is on a clearly

unsustainable trajectory. The IMF public debt projections fail to consider the impact on public

debt trajectory of the external adjustment that is necessary to assure a

sustainable external debt trajectory. The IMF external debt projections contained

in the review reports are in my view, not realistic and not feasible at all.

But that is a subject for another discussion.

*revised version.

*revised version.

Saturday, 10 November 2012

The War of the Multipliers

One month ago, the IMF presented evidence that structural macro econometrics models used by international organisations are underestimating current fiscal multipliers. Last week the European Commission presented evidence that focusing on the euro area the IMF results need to be interpreted with caution. To EC study acknowledges that there are good reasons why the fiscal multipliers can be larger in the current environment but also says that she finds no evidence of underestimation of those, al least when focusing on the euro area countries.

More precisely the EC study argues that (I quote):

1."the forecast errors over the 2010-11 period have been predominantly underestimations of higher-than-expected growth in 2010, which were in fact associated with stimulus measures in that year";

2. "when controlling for increases in sovereign-bond yields the correlation between forecast errors and changes in the fiscal stance breaks down."

Reason 1. says that the fiscal multipliers may be underestimated, but this is due to countries that have adopted a stimulative fiscal stance (I would add: good for them!). Furthermore these stimuli are temporary in nature and imply higher multipliers than those due to permanent fiscal consolidations.

The empirical exercise is performed using structural fiscal balance, a measure that is constructed to filter out temporary factors from the actual fiscal balance. The reason why negative forecast errors in the structural fiscal stance are associated with temporary fiscal changes while positive forecast errors in the structural fiscal stance are associated with permanent fiscal changes eludes me. If this was true I would look at structural fiscal balance measures suspiciously.

Reason 2 is harder. In the EC study, adding as an explanatory variable the change in government yields, the underestimation result disappears.

The explanation is as follows:

"…the negative coefficient for the fiscal stance in the first regression should not be interpreted as an underestimation of the fiscal multiplier but rather as capturing a negative response of investors to possibly insufficient fiscal effort in countries with severe debt problems."

I would argue that the case for reverse causality is strong: were the yields reflecting the preoccupation of the markets for a not strong enough fiscal consolidation or for a not strong enough economic growth? In the latter case the regression suffers from an endogeneity problem (see IMF footnote 3) and the coefficients estimates would be biased.

Here I report the benchmark results using the IMF and the EC data for the euro area countries. (GFE is cumulated growth forecast errors and FCFE is cumulated fiscal consolidation forecast errors).

Notice how the estimates are close. The main differences in the two datasets appear to be: 1. the presence of Luxembourg in the EC data, and 2. a significant difference (sign and size) in the forecast error of the fiscal consolidation of Ireland.

Tuesday, 6 November 2012

Advertisement: a site for "probing into the Portuguese Economy"

I just browsed it, but so far it looks incredibly useful: http://www.peprobe.com.

Monday, 5 November 2012

Are we going Greek?

In May 2010, the troika announced a rescue plan for Greece. Ireland followed in November 2010. In May 2011 it was time for Portugal to be bailed out. In July 2012, Spain received special assistance for its banks - more is expected to come.

One of the main questions concerning these economies is: How similar is their evolution? In other words, if we look at one of them, will we be able to say what happened, or what is happening, or what will happen to the other economies?

Greece has been at the centre of the euro area sovereign debt crisis. Private holders of Greek bonds have already suffered a haircut. Exit from the eurozone is openly discussed. In Portugal, many voices have expressed concern at the possibility that austerity measures will make Portugal tread in Greece's footsteps. Nuno Garoupa, for instance, wrote that Portugal lags Greece by eighteen months.

In this webpage we report data on the bailed-out economies in order to allow the evaluation of the similarities among them. The closer other countries replicate Greece's path, the closer the euro will be to its end.

At the time of writing, the indicators presented below show that Greece stands out for its worse performance among this group of countries, except for private debt - where Ireland reports the largest ratio to GDP - and for the net international investment position - where Portugal performs worse.

(with Pedro Bação, University of Coimbra)

Sunday, 28 October 2012

Until debt tear us apart?

Every

month I do an analysis for newspaper Público of the implementation of the

budget accounts (see

here in Portuguese article 25/10/2012) based on historical records for each

major item of revenues and expenditures, tax elasticities, detailed analysis of

the data, etc..

It is

very important to be aware of the implementation of the fiscal consolidation programme

to understand whether fiscal measures are leading us to the desired lowering of

public deficit in order to reduce Portuguese net borrowing requirements or not.

Starting

with the simplest indicator – general government balance – the answer is no.

Public deficit in 2011 (in national accounts), without one-off measures was

5,8% of GDP and in 2012 my estimate is 5,9%.

The fiscal

strategy of the Portuguese Government (under pressure of ECB/EC/IMF –the troika)

was a severe cut in public expenditures through two major items (cut of two

subsidies of pensioners and civil servants) and other smaller items of

expenditure and to raise several taxes, more through an increase in tax rates

than in tax bases.

It is now

clear that this strategy is not working. If the use of instruments does not

achieve the target it is because the strategy is flawed. The social situation is

getting worst, unemployment is rising, bankruptcy of firms is increasing, civil

servants are frustrated with wage cuts and no career prospects, and yet …public

deficit is not decreasing. However, neither the government nor the troika still

recognizes this.

|

|

MF

|

PTP

|

|

Deficit 2012 State Budget

Rectified(1)

|

4,5

|

4,5

|

|

Lower tax revenues

|

1,6

|

2,1

|

|

Budget overestimation of

central governments' Wages

|

|

-0,4

|

|

Variation in Social Security

Accounts

|

0,6

|

0

|

|

Other

|

|

-0,3

|

|

Total

|

6,7

|

5,9

|

|

One-off measures (PTP) or

savings (MF)

|

-1,7

|

-0,9

|

|

Défice 2012 OER(2)

|

5

|

5

|

|

Source: MF -Ministry of

Finance, PTP-Paulo Trigo Pereira - own

calculations

|

||

|

Estimates of deviations from

budget target (% of GDP). Negative

deviation decreases deficit.

|

||

(see

detailed explanation and further information in the Portuguese article).

Curiously

Portugal will have a surplus in the primary balance in 2012 (excluding

interests of the debt). With a ratio of debt to GDP approaching 120% and a

recession, unless there is a sharp and quick decline on the interests of the

debt or Portugal will not be able to repay the principal. The ECB should

anticipate the intervention in countries with adjustment programmes (under OTR)

in order to decrease the interests of the debt. It seems

the only reasonable solution.

PS The IMF just released the 5th evaulation of the Adjustment Programme. It deserves a further scrutinity here...

Thursday, 25 October 2012

MoU, 5th update

The new update on the Memorandum of Understanding is now available here, observations and comments to come in the near future.

Wednesday, 24 October 2012

La raison on Fiscal Devaluation

A piece by prominent French Economists on the fiscal devaluation, que dis-je, une devaluation fiscale!

click

click

Wednesday, 3 October 2012

The Roots of the Euro Crisis Lie at the Doorsteps of the ECB

I have written a column, published in EconoMonitor, which argues that deficiencies in the Eurosystem monetary policy contributed to the “euro crisis”, which is, in reality, an intra-Eurozone balance of payments and external debt crisis. It claims that the Eurosystem’s monetary policy instruments and procedures allowed intra-Eurozone external imbalances to accumulate since the start of the third phase of the EMU in January 1, 1999. As a result, though the Eurozone has low levels of net external debt relative to its GDP, it presently confronts, in its midst, what is likely the largest peacetime external debt crisis the World has ever seen. Moreover, it points out that the Eurosystem’s monetary policy has always had large fiscal effects and currently results in financial transfers from Eurozone creditor countries (the GNLF) to Eurozone debtor countries (the GIIPS) that may amount to 1.3% of the GIIPS’ combined GDP per year.

Please see full post here.

On the subject of how the ECB has recently (ab)used its vast (unlimited?) powers I recommend the reading of the following column by Karl Whelan.

Fiscal devaluation à la façon du chef

France is probably the next country to use a decrease in the employers' payroll taxes to boost competitiveness. How is it going to be financed? It is not clear yet, but according to Le Monde http://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2012/10/03/cout-du-travail-ce-que-prepare-l-elysee_1769200_823448.html this could be done via the Contribution Sociale Généralisée, which is basically an income tax falling on all sorts of income and taxable gains (including earned and pension income, property rental, investment income, bank interest and capital gains). It is also likely to be targeted only at average wages (between 1.6 and 2.2 times the minimum wage), a novelty with respect to the former proposition which targeted the left tail of the wage distribution. The proposal is still in its very early stages, so many things can still be fine tuned. But it could be bad news for Portugal if our European partners manage to decrease their labor costs in innovative ways...

Thursday, 27 September 2012

Measures rather than targets

An interesting statement by Christine Lagarde:

"On the Fund’s part, we are favorably considering that this be done in as timely and flexible a manner as possible: slowing the pace of fiscal adjustment where needed; focusing on measures rather than targets..."

Success of this strategy relies on the level of confidence and consensus on "measures". One possibility is to express the targets in intervals that reflect the uncertainty on "measures". By settling on the level of uncertainty we could gain flexibility and accept the realization of a slower path of adjustment.

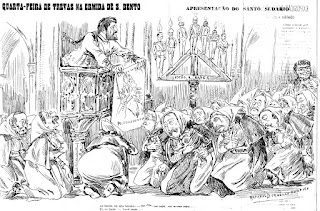

São Bento Revisited - Fiscal Consolidation 19th Century Style

Now that the government gave up

on the idea of fiscal devaluation and decided to fall back on fiscal

consolidation and, more recently, poetry, the press is awash with speculation about the

raft of alternative fiscal measures to be introduced in the new budget. Some time ago I commented on the remarkable similarities between our current financial

problems and what arguably was our most serious financial crisis in modern

times – the 1892 default. After attempting to do something completely

different, the government now seems constrained by the corset of short-term

fiscal expediency that requires immediate tax increases (perhaps with increased progressivity) and expenditure cuts where feasible, though not necessarily more

efficient.

Reading the press, I was struck

once more by how the likely options of this government resemble the choices

followed in 1892. Maybe there was no learning over 120 years of public finance

in Portugal – or perhaps the co-dependency relation between state and economy,

very obvious in the nineteenth century, is essentially still there today.

The TSU (Social Security Contributions) measure: a political post-mortem

The Portuguese government backed down from the proposed measure to increase employee's social

security contributions and decrease

employers' contributions. A measure that manages to elicit the opposition of the Portuguese left-wing parties, the unions, employers' associations, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Wall Street Journal is certainly unusual. Let me speculate a bit - and let me stress speculate - on causes and consequences.

1. Part of it was probably just a series of mistakes, either unforced or, most likely, forced by the context of the Troika evaluation, inter-coalition relations, and government coordination problems. The measure was announced without any background studies legitimating it or documents explaining it in detail, leading the media to engage for days in wild and contradictory guesses about its consequences (the only study of the impact of this specific measure I know of was made by a group of economists of Minho and Coimbra). The government even failed to ensure that, in the immediate aftermath of the announcement, at least a few voices would come in its defense, either from within the PSD or (especially) from the coalition party, the CDS-PP. Instead, what it got was a barrage of criticism not only from the opposition but also from notable figures of the PSD and from its coalition partner. It is difficult to recall a single respected political figure, scholar, or expert that came in the measure's defense. In reaction to this, the government kept introducing nuances to the measure that seemed to be made up as it went along. From the political marketing/communication point of view, the whole thing was abysmally managed. Voters may have difficulties in understanding the implications of these sorts of measures beyond the very evident fact that their paycheck will be smaller, but they have no difficulty in looking around for cues from reliable sources in order to form their opinions. And so they did: a week later, 78% of respondents in a public opinion poll disagreed with the notion that the reduction of companies' social security contributions would help fighting unemployment, while 81% disagreed with the notion this would have an impact on consumer prices. Game over.

2. There was probably also some amount of hubris involved. It may be the case that some people in the government or in the group of government advisers are persuaded that the 2011 election and the PSD's victory meant some sort of vindication of a "liberal," "market-friendly," or "business-friendly" agenda. If that's the case, I'm afraid they are likely to be sorely mistaken. The data from the 2011 post-election study shows that voters' positions in these issues have remain unchanged since at least the early 2000s, and that such positions were furthermore completely irrelevant in their vote choices. This means that the PS's effort to turn the election into an ideological "fight for the survival of the welfare state" was a failure, but also that the election did not mean in any way a legitimation of the PSD's ideological agenda either. Furthermore, anyone who has ever looked at surveys measuring Portuguese voters' views about social inequality and work relations would easily guess that any measure that could be construed as "shifting money from workers to employers" would have close to zero chances of eliciting any sort of relevant support.

3. We should not forget that the government's problems did not start in September 7th. The government had a horrible summer, most notably a media barrage against minister Miguel Relvas and his alleged ethical and legal problems. Then, the plan for privatization of public television - led precisely by Relvas - managed to mobilize an influential sector of opinion - cultural and media agents - that are not exactly known for their love of the Right. A lot of badly needed political capital was wasted on these side issues.

4. There's also an element of the government's discourse since the very beginning that is probably counterproductive. The vaguely populist message entailed in the "smallest government ever" thing and on the emphasis on "fighting waste" and "trimming the fat" in the state apparatus, together with regular and ill-advised promises that economic recovery is coming "next year", probably did not help making voters quite prepared for real magnitude of the problems faced, for the failures in meeting the deficit targets, and for the many additional austerity measures that will be necessary in order to meet them. Correct management of expectations is much more important that giving false "glimmers of hope" or pretending that "trimming fat" is what this whole thing is about. We're in this for the long haul, and everybody hates realizing they may have been deceived.

5. The future holds dangers. I leave the economic dimension to my colleagues here, but it seems clear that the marriage between the PSD and and CDS-PP is becoming more and more a marriage of convenience, plagued by mutual distrust. Minister Relvas has been mortally wounded for a few months now, but it is unclear who is supposed to perform his political coordination role when (we're way past the "if" question) he ends up being replaced. It is also a bit of a mystery how Mota Soares, the CDS-PP social security minister, who supported the TSU measure only to face his own party's leader disagreement a few days later, finds it appropriate to remain in the cabinet. Some of these problems can be solved with a cabinet reshuffle after the approval of the 2013 budget, but the legacy of mistrust between the parties and the way the "governability" image of Portugal was tarnished will be difficult to reverse.

6. But not all is bad news. There's no obvious alternative political solution to the current coalition. Most voters seem to agree with that. The somewhat unpopular President, Cavaco Silva, played nonetheless a crucial role in defusing the crisis brought about by the TSU measure. The fact that the government was able and willing to back down from the TSU measure is a very positive sign. Demonstrations have been large and reveal anger and disappointment, but they have been peaceful, and so have the relations with police forces. The Minister of Finance's comments about the demonstrations, praising their moderation and dignity, were impeccable. The contrast with Spain, not to mention Greece, is quite instructive. Robert Fishman, a political sociologist, has a wonderful article in which, among other things, he shows stark and unexpected contrasts between Portugal and Spain in what concerns the relationship between protesters and institutional power holders and the role and acceptance of mass mobilization in Portugal. The recent events are a nice confirmation of Robert's ideas.

1. Part of it was probably just a series of mistakes, either unforced or, most likely, forced by the context of the Troika evaluation, inter-coalition relations, and government coordination problems. The measure was announced without any background studies legitimating it or documents explaining it in detail, leading the media to engage for days in wild and contradictory guesses about its consequences (the only study of the impact of this specific measure I know of was made by a group of economists of Minho and Coimbra). The government even failed to ensure that, in the immediate aftermath of the announcement, at least a few voices would come in its defense, either from within the PSD or (especially) from the coalition party, the CDS-PP. Instead, what it got was a barrage of criticism not only from the opposition but also from notable figures of the PSD and from its coalition partner. It is difficult to recall a single respected political figure, scholar, or expert that came in the measure's defense. In reaction to this, the government kept introducing nuances to the measure that seemed to be made up as it went along. From the political marketing/communication point of view, the whole thing was abysmally managed. Voters may have difficulties in understanding the implications of these sorts of measures beyond the very evident fact that their paycheck will be smaller, but they have no difficulty in looking around for cues from reliable sources in order to form their opinions. And so they did: a week later, 78% of respondents in a public opinion poll disagreed with the notion that the reduction of companies' social security contributions would help fighting unemployment, while 81% disagreed with the notion this would have an impact on consumer prices. Game over.

2. There was probably also some amount of hubris involved. It may be the case that some people in the government or in the group of government advisers are persuaded that the 2011 election and the PSD's victory meant some sort of vindication of a "liberal," "market-friendly," or "business-friendly" agenda. If that's the case, I'm afraid they are likely to be sorely mistaken. The data from the 2011 post-election study shows that voters' positions in these issues have remain unchanged since at least the early 2000s, and that such positions were furthermore completely irrelevant in their vote choices. This means that the PS's effort to turn the election into an ideological "fight for the survival of the welfare state" was a failure, but also that the election did not mean in any way a legitimation of the PSD's ideological agenda either. Furthermore, anyone who has ever looked at surveys measuring Portuguese voters' views about social inequality and work relations would easily guess that any measure that could be construed as "shifting money from workers to employers" would have close to zero chances of eliciting any sort of relevant support.

3. We should not forget that the government's problems did not start in September 7th. The government had a horrible summer, most notably a media barrage against minister Miguel Relvas and his alleged ethical and legal problems. Then, the plan for privatization of public television - led precisely by Relvas - managed to mobilize an influential sector of opinion - cultural and media agents - that are not exactly known for their love of the Right. A lot of badly needed political capital was wasted on these side issues.

4. There's also an element of the government's discourse since the very beginning that is probably counterproductive. The vaguely populist message entailed in the "smallest government ever" thing and on the emphasis on "fighting waste" and "trimming the fat" in the state apparatus, together with regular and ill-advised promises that economic recovery is coming "next year", probably did not help making voters quite prepared for real magnitude of the problems faced, for the failures in meeting the deficit targets, and for the many additional austerity measures that will be necessary in order to meet them. Correct management of expectations is much more important that giving false "glimmers of hope" or pretending that "trimming fat" is what this whole thing is about. We're in this for the long haul, and everybody hates realizing they may have been deceived.

5. The future holds dangers. I leave the economic dimension to my colleagues here, but it seems clear that the marriage between the PSD and and CDS-PP is becoming more and more a marriage of convenience, plagued by mutual distrust. Minister Relvas has been mortally wounded for a few months now, but it is unclear who is supposed to perform his political coordination role when (we're way past the "if" question) he ends up being replaced. It is also a bit of a mystery how Mota Soares, the CDS-PP social security minister, who supported the TSU measure only to face his own party's leader disagreement a few days later, finds it appropriate to remain in the cabinet. Some of these problems can be solved with a cabinet reshuffle after the approval of the 2013 budget, but the legacy of mistrust between the parties and the way the "governability" image of Portugal was tarnished will be difficult to reverse.

6. But not all is bad news. There's no obvious alternative political solution to the current coalition. Most voters seem to agree with that. The somewhat unpopular President, Cavaco Silva, played nonetheless a crucial role in defusing the crisis brought about by the TSU measure. The fact that the government was able and willing to back down from the TSU measure is a very positive sign. Demonstrations have been large and reveal anger and disappointment, but they have been peaceful, and so have the relations with police forces. The Minister of Finance's comments about the demonstrations, praising their moderation and dignity, were impeccable. The contrast with Spain, not to mention Greece, is quite instructive. Robert Fishman, a political sociologist, has a wonderful article in which, among other things, he shows stark and unexpected contrasts between Portugal and Spain in what concerns the relationship between protesters and institutional power holders and the role and acceptance of mass mobilization in Portugal. The recent events are a nice confirmation of Robert's ideas.

Tuesday, 25 September 2012

The U-turn

Mind you, the U-turn by the Portuguese Government reveals more about its internal functioning than about its determination to proceed with the Memorandum agenda. The proposed changes in the Social Security Contributions (TSU) were designed by a small inner circle of a couple of cabinet members and a few other government advisors, and they were made under the impression that public opinion and opinion polls didn't matter. Certainly that the Prime Minister was aware of what was going on, but he did not pay enough attention to the true extent of the proposed measure as he notably trusted those in charge for the plan. The U-turn has to be analyzed in that context. The proposed measure - which would have implied a direct income transfer from employees to employers - was indeed outrageous. The way the Government is doing its business didn't allow for the necessary political control. There is no need now to put further pressure on the Portuguese Government so that it proves its willingness to proceed with the troika Memorandum - for the sake of the Portuguese public. What we need now is pressure on the Government so that it pays more attention to the fact that too much austerity is counterproductive, as the IMF and other institutions have been saying for more than a year now.

PS: an excellent follow-up.

PS: an excellent follow-up.

Portugal Real Exchange Rate in the EZ

Flashback

From 1995 to 2001 the large decrease in nominal interest rate (panel 1) fueled an expansion in private expenditure (panel 2) financed with debt (panel 3) while the increase in demand pushed nominal labor compensation to ran a rate of 6 percent per annum, a rate well above labor productivity, and GDP inflation to increase to 4 percent per annum. The result was a large and rapid loss in competitiveness vis-a-vis the eurozone partners (panel 4). During and after the recession of 2002, labor compensation and final prices inflation decelerated, but not sufficiently, and Portugal competitiveness continued to, this time slowly, deteriorate against the other eurozone members (panel 4). (click to enlarge)

Competitiveness

A measure of REER based on ULC vis-a-vis the rest of the eurozone, normalized to 100 in 1995, was at 83.4 in the the fourth quarter 2011 implying a cumulative loss of 16.6 pp. A similar measure based on GDP deflators was at 88.3 implying a cumulative loss of 11.8 pp.

Consequences ?

The observation that the real exchange rates remained misaligned so persistently (the GDP deflator REER moved very little since the starting of the euro) leads to the following question: will the REER have to adjust back to the 1995 level or even overshoot to remedy the accumulated consequences of overvaluation? One argument for overshooting is that the accumulation of net external debt means that the current account cannot be balanced simply by returning to the initial real exchange rate. Now there is a deficit stemming from the increased debt service (and much lower remittances). Therefore, to restore current account balance, an over-depreciation might be required. However not every model/economist agrees on the necessity of the REER adjustment. Another old dispute.

P.S.

One has to remark that last year current account adjustment has been extraordinary and mainly driven by net exports. An interesting question is to explain how this improvement occurred.

P.S.

One has to remark that last year current account adjustment has been extraordinary and mainly driven by net exports. An interesting question is to explain how this improvement occurred.

Sunday, 23 September 2012

The poll tax moment of the Portuguese government

As I wrote in my last weekly column in Dinheiro Vivo, the government of Mr. Passos Coelho just went through its "poll tax" moment. As Mrs. Thatcher, more than twenty years ago, the government tried to implement an economic policy that (i) makes sense in some simple models of the economy, (ii) but has ambiguous effects once you change a few assumptions, (iii) was not progressive and because of that was politically toxic, (iv) led to widespread social protest, (v) and turned part of his own party and coalition against him.

Unlike Mrs. T, Mr. Passos Coelho seems to have been wise enough to move back before it was too late. Whether one agrees with the economic merits of the measure or not, kudos to him for stepping back from the trap that the great Mrs. Thatcher fell right into. Only time will show what the long-run consequences of this mis-step will be.

Unlike Mrs. T, Mr. Passos Coelho seems to have been wise enough to move back before it was too late. Whether one agrees with the economic merits of the measure or not, kudos to him for stepping back from the trap that the great Mrs. Thatcher fell right into. Only time will show what the long-run consequences of this mis-step will be.

Wednesday, 19 September 2012

How rich are the richest? The top income bracket for Personal Income Tax purposes

My previous post raised the question of whether the highest marginal taxes apply to income brackets which are not too high. Increasing these marginal taxes could then penalize the middle class. Two comments: firstly, my claim for increased progressivity obviously includes changing both the marginal tax rates and the income brackets to which they apply, if needed. Secondly, the highest marginal tax rates actually apply to relatively high incomes. The standard way in which the OECD measures this feature of the tax system is the ratio between the lowest income value to which the top marginal tax rate applies and the average wage of the country. In Portugal, this figure amounts to 9.7, as of 2010. Only Chile has a higher score than Portugal in this regard. The differences between the Personal Income Tax schedule applied in 2010 and 2011 are too small to change this figure significantly.

Let me stress that this is a rather partial view on progressivity. A tax reform aimed at increasing progressivity may use both the definition of the income brackets and the marginal tax rates applying to each of them.

| Source: OECD, Taxing Wages, 2012 |

Let me stress that this is a rather partial view on progressivity. A tax reform aimed at increasing progressivity may use both the definition of the income brackets and the marginal tax rates applying to each of them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)